Friday

May282010

Matlin's America: So What is This "Special Relationship" with Britain?

Friday, May 28, 2010 at 18:04

Friday, May 28, 2010 at 18:04  Every time there is a change of leader in the United Kingdom or the US, the British media jump to the question of when the new man (or woman) will meet his or her counterpart and the extent to which the so-called “special relationship” between the countries will benefit or suffer.

Every time there is a change of leader in the United Kingdom or the US, the British media jump to the question of when the new man (or woman) will meet his or her counterpart and the extent to which the so-called “special relationship” between the countries will benefit or suffer.Hence when Bill Clinton, with whom Tony Blair seemed to enjoy the best of relationships, was succeeded by George W. Bush, the media expected the “SR” to be damaged. Blair, by then everybody’s friend (at least in the West), did his “May I call you George?” bit, and all seemed to be well.

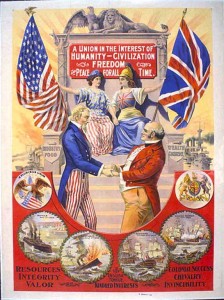

This special relationship between Britain and the US is much misunderstood and misinterpreted. The term attempts to encapsulate close political, cultural, and historical tie, yet it did not exist, even as media commentary, at the end of the First World War. Let us not forget that part of America’s price of entering the war was the sharing of British bunkering ports throughout the Pacific and elsewhere, a privilege previously denied to the US. The aim was to break the trading power of the British Empire.

America repeated its assault at the end of World War II. Certainly, Britain was the largest recipient of aid under the Marshall Plan but much of that was passed on to other European countries. And, boy, did we pay for the support in higher interest rates and stricter terms than other recipients. Indeed, we only repaid the final installment of Marshall aid a few years ago.

Let me be clear. I don’t object to what the US did in exacting a price from its allies. Business is business. What needs to be said is that in the days of world conflict and its aftermath, America’s overriding policy was free trade; the British Empire’s policy was preferential trade. The economic difference between the two nations mitigated against any so-called special relationship.

One cannot ignore the personal. I am positive that Franklin D. Roosevelt liked Winston Churchill, whilst resisting the latter’s overtures to join in the fight against Germany before December 1941. I have no doubt that Harry Truman liked Winnie, too. Indeed, it was during Churchill’s famous 1946 "Iron Curtain" speech in Fulton, Missouri that the expression, “special relationship” was allegedly coined. But can anyone point me to US policy decisions, in those first years after World War II, that demonstrate the existence of this special relationship?

In the early 1960s, Harold Macmillan thought John F. Kennedy was wet behind the ears and a man who could be led by them. Even after Kennedy showed Macmillan the error of this judgment, the two men remained on good terms. However, Lyndon Johnson's relationship with Harold Wilson was strained. LBJ tried to get Wilson to send a small, token force to Vietnam, in exchange for which he would help bail the Brits out of yet another economic crisis, but for once Johnson’s charm offensive failed. Wilson would not play ball in Southeast Asia.

And now? President Obama demonstrated his disdain for Prime Minister Gordon Brown by refusing one-to-one meetings or even a photo call.

At the highest levels, the special relationship doesn’t really exist, except as a personal link, and even then, nothing is certain.

Take an occasion two weeks ago. A U.S. Senate committee called in the Chief Executive Office of BP America to explain the company’s role in the explosion and leak of the Gulf of Mexico oil wellhead. The CEO found himself facing a firing squad, with one senator after another seeking absolute confirmation that BP accepted full liability for the leak and would pay all claims, regardless of actual fault.

The senators did not like the CEO’s response that BP would pay all claims for which it was legally responsible. The US legislators were out for blood and I’m sure they were even keener than usual to get a foreign company spiked. (I have not seen American corporations, even US commercial bankers, treated this way by the Senate.)

I do not seek to excuse BP in any way from their acts or omissions. But let's be clear --- as many of the senators involved knew full well that an admission of liability would negate insurance policies, enabling BP’s insurers to walk away, as the company tried to protect its shareholders --- during the hearings, no one referred to any special relationship between the US Government and a British company.

I believe in the existence of the special relationship. It is at grassroots level. The British and Americans share a common language, or at least a resemblance of a common language. of sorts. Generally, the people of each nation are pro-famil and centre of the road politically, have a keen enjoyment of sports and arts, and are charitably and socially minded.

I have relatives in New York and Miami. I have an American wife and enjoy seeing her extended family, be they in Minnesota, Oregon, Arizona, California, or New York.We have close American friends from Vermont to Colorado. I visited the on business for more than 40 years, probably more than 150 times. Since retirement, I have had extended stays for academic research. On all such visits, and I do mean all, I was treated as a friend should be.

US ideology is often quite different to ours. The British, by and large, are not hung up on issues such as abortion or creationism, nor are we troubled by same-sex unions. And we don’t want to carry guns. In return, some Americans might say we Brits have no concept of advanced citizenship.

But these differences are outweighed easily by what I like. In their locality, Americans tend to be socially-minded. They care about their neighbours and friends. They are amazingly charitable. Their restaurants (excluding the fast-food empires) usually serve great food at reasonable prices. I have a list of places to recommend from Miami to Seattle. And there’s so much space in America, as opposed to the little island where I live.

Freedom is a reality. And because our two peoples have so much in common, the special relationship is alive and well, even if our governments are at each others' throats.