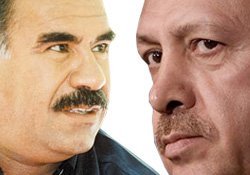

Abdullah Ocalan and Recep Tayyip ErdoganThe Politics of the Funerals

Abdullah Ocalan and Recep Tayyip ErdoganThe Politics of the Funerals

Last week, tens of thousands of mourners bade farewell to three Kurdish activists assassinated in Paris.

In Batikent Square in Diyarbakir in southeastern Turkey --- "a political centre" of the Kurdish, in the words of Peace and Democracy Party (BDP) co-chair Selahattin Demirtas --- a BDP member of Parliament, Ahmet Turk addressed the crowd, criticising the government with finely-balanced language:

At a time when peace is discussed, everyone is expecting sensitivity from the Kurds. Despite of our three losses, our people want peace. However, those who ask for sensitivity are bombing Kandil [in northern Iraq, where fighters of the PKK insurgency are based]. What kind of politics is this? You both talk about peace and bomb the Kurds. The Turkish people must see this, see who sides with peace.

Demirtas continued to stress the expectations from the Kurdish side:

What is the guarantee put forth by you? Put a step forward, bring something tangible. In these days we are talking about peace, 11 funerals are waiting in the morgue of Malatya hospital and there are other 7 in Kandil. You can't both wage war and make peace. The will you wanted to destroy has become millions from Paris to here, flooded like a stream.

Demirtas, who called on European states to put pressure on the government, said currentpeace talks were different than previous efforts and summarized his agenda in two main points: the Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK) --- banned by the Government --- must take the lead in the region and Iraq Kurdistan Regional Government leader Masoud Barzani must be included in the process.

A New Era in the Kurdish Question?

In the four-stage plan of this peace process, the imprisoned leader of the Kurdish PKK insurgency, llah Ocalan, could be rewarded with a move to house arrest, general amnesty for PKK members, and further "democratic" Constitutional reforms. In return, PKK fighters will leave Turkish territory and disarmi in northern Iraq. Perhaps surprisingly, Ocalan is giving up the ambition of "administrative autonomy" in return for a neutral definition of citizenship in the Constitution --- no preference for "Turks" --- the right to education in a mother language, and consolidation of local administrations.

All well and good except that during the negotiations, the Government has to display an upper hand which reveals itself with daily detentions and military operations. If a peace deal is to be completed, there will have to be some impediment to the Government's unrestricted use of its power.

Demirtas has not focused on this. Instead, his references to the KCK and Barzani are part of the long-term goal of Kurdish "liberation" with Constitutional guarantees in four countries and a union around cultural, economic, and political activists. Those ambitions follow those of Ocalan in his "Kurdistan-Revolution Manifesto."

The challenges to that goal go beyond Ankara. The first is over the crisis in Syria --- indirectly involving Iran --- where the Erdogan Government has no intention of repairing times with Syrian Kurds of the Democratic Union Party. The second is the inclusion of Iraq's Barzani in a political process: it is unclear what incentive Ankara has to acknowledge, let alone accept, the BDP's demand.

It appears, however, that the Turkish opposition party will persist. Barzani's participation would bolster the BDP's diplomatic power. It could consolidate the future arrangements over the PKK, allowing its presence in northern Iraq while "containing" it from attacks and threats either to the Turkish military or to Iraqi Kurdish forces.

Meanwhile, a high-profile relationship between the BDP and Barzani would elevate the "Kurdish project" beyond a single country. It is no coincident that it was Barzani who brought the Kurdistan National Council (KNC) and Syria's PYD under an umbrella arragnement last July with the Hewler Agreement. So the BDP's initiative covers not one or two but three countries: a Turkish-Iraqi-Syrian political arrangement.