David D. Kirkpatrick writes for The New York Times:

David D. Kirkpatrick writes for The New York Times:

Even the mildest criticism of the Egyptian military was too much for Mahmoud Saad, a television host on the newly founded, independent Tahrir television network.

“Any institution of the country that takes taxes from us should be open to question,” Hossam el-Hamalawy, a blogger, said in an interview with Mr. Saad.

“No, no, no,” Mr. Saad interrupted. “I will not allow you to say those things on this network.”

“Thank you, Mr. Hossam,” he declared, hanging up.

The next day Mr. Hamalawy and two other liberal television journalists, but not Mr. Saad, were summoned to a military headquarters for questioning about their remarks.

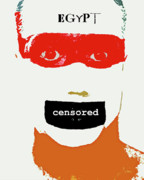

The Egyptian military — facing public criticism for torturing demonstrators and admitting that it forced some female detainees to undergo “virginity tests” — is pressing the Egyptian news media to censor harsh criticism of it and protect its image. The military’s intervention concerns some human rights advocates who say they are worried that such efforts could make it harder for politicians to scrutinize the military and could possibly undermine attempts to bring it under civilian control or investigate charges of corruption.

“Nobody believes corruption was limited to the civilian government,” said a prominent liberal politician, speaking on the condition of anonymity out of fear of reprisal by the military.

In recent weeks military authorities have sent letters warning news organizations to review any discussion of the military before publication or broadcast. A military court has also sentenced a blogger to three years in prison for what it called persistent attacks, and it has charged an outspoken liberal presidential candidate with libeling a general and insulting the military. Military authorities have summoned many journalists and bloggers to headquarters for questioning about their reports and sources.

In a recent interview, a military official, demanding anonymity in keeping with military protocol, insisted that the military accepted the public’s right to criticize while it was playing the political role as Egypt’s interim ruler. But he said the military also sought to balance “freedom of expression” against “respect for the institution,” drawing the distinction between criticizing individuals and insulting either those people or their institution.

“If someone presents proof that any officer is corrupt, then the officer would be subject to the law; if he doesn’t present any evidence, then the journalist would be subject to the law,” he explained. “If I call you a dictator, you can take that as an insult.”

In short, he added, “criticize the military, but be sure of what you are saying.”

For his part, Mr. Hamalawy said the military’s request to question him was intended as intimidation; he said he was asked about evidence related to the torture of demonstrators that had already been made public in legal complaints, as well as online.

He said, “When the military says ‘please show up,’ it is kind of like an order, especially when they are ruling the country.”